The pain goes on. The Met Office announced yesterday that they are giving up seasonal forecasts. This is going to seem to most people – and I have to go along with the majority view on this – as if there’s something seriously wrong. I don’t believe we’re dealing with butterflies’ wings here. I simply don’t understand why it’s not possible to provide a broad brush indication of the weather in a coming winter or summer. Presumably the right data is not available, and, from a cursory reading of the literature, what’s needed is a better picture of ocean temperatures at different depths. I suggest that’s where resources must be focussed (and I gather plans are indeed afoot – codename Argo). Because climate science needs to get out of the dog-house.

Managing the message

What we certainly don’t need is another PR disaster.

If Professor Latif’s prediction of a period of a decade or more of cooling either imminently or over the next decade or two is correct, then “we’ll have to eat crow” as one comment on a New Scientist article put it. The expectation of what Latif terms “monotonic” – presumably meaning “steady” or “linear” – global warming has been set.

Furthermore, as I stressed before, the reliance on Arctic sea-ice as an indicator is unwise, to say the least. The Guardian’s report of the Met Office’s latest assessment of the evidence gave prominence to the Arctic sea-ice graph yet again yesterday.

The Guardian also included a commentary by a Dr Chris Huntingford, the online title “How public trust in climate scientists can be restored” making a lot more sense than “We need to look beyond temperature” in the print version. Huntingford makes the point that:

“To preserve public confidence, we must ‘buy out’ the copyright from research journals of key papers so that these can be freely available to all for inspection. Datasets must also become more available for general scrutiny.”

Too right. I found myself this week in the British Library accessing a paper by Drs Phil Jones and Ken Briffa, yes that Phil Jones from the CRU at UAE, Dr Emailgate himself.

What I was interested in was what Jones and Briffa term the “Unusual climate in Northwest Europe during the period 1730 to 1745”. Before I report their findings, I’ll explain why I was interested in 1740 in the first place.

The 1740 Anomaly

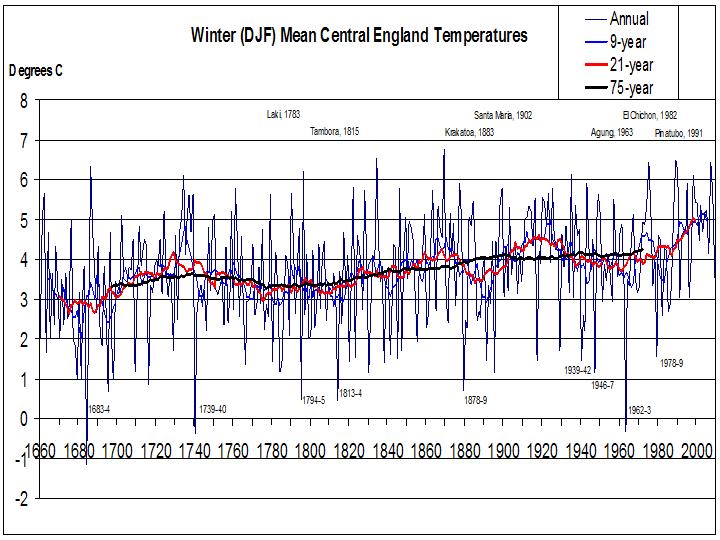

In my last post I presented a graph of the Central England Temperature (CET) record from 1659 to 2009. I noted the cold winter of 1739-40 which occurred after the famously warm decade of the 1730s, with a run of winters as mild as anything that occurred before the globally warmed world of the last decade (though the 1920s is also comparable).

I wanted to see how anomalous 1739-40 was, so I replotted my graph with a longer running mean. In fact, I did several plots, but let’s consider the one with a 75-year running mean, which smooths out all but long-term temperature trends:

I then calculated the Standard Deviation (SD) of the winter 1739-40 temperature against the 75-year running mean. The 1739-40 winter was 3.14 SDs colder at -0.4C than the running mean (5.59C). A statistical table tells us that we should only expect such an anomalously cold winter about once every 1,100 years. Yet a couple of centuries later 1962-3 came along and, although marginally milder, this was against a higher 75-year running mean, so was a once in nearly 5,000 years event. It seems something non-random is going on.

Curiously, the 9-year running mean of winters from 1730-1 to 1738-9 was, at 4.81C, even more anomalous than the 1739-40 winter. It was 3.27 SDs warmer than the 75-year running mean centred on 1735 (3.58C). (Obviously, there is less deviation in 9-year means than of single year temperatures from the long-term mean so the SD is lower). If temperature fluctuations were random and normally distributed, you would only expect a run of 9 winters as mild as 1730-1 to 1738-9 about once in nearly 2,000 years.

So we had a once in 2,000 year series of mild winters followed by a once in 1,100 years cold winter. Curiouser and curiouser…

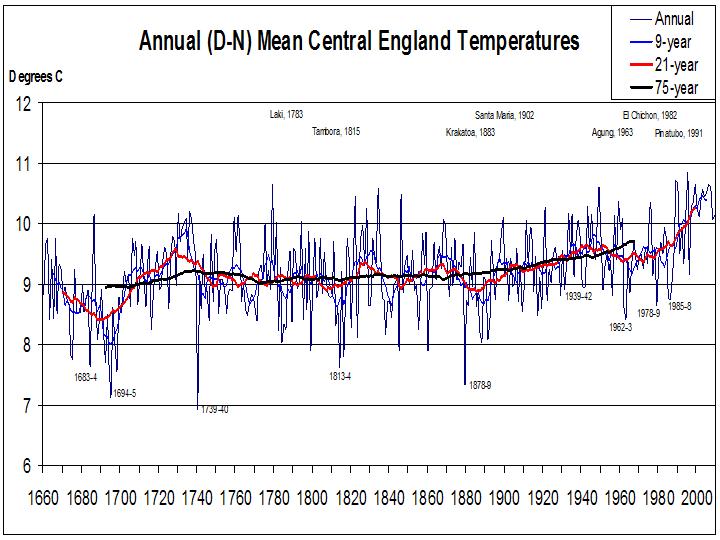

Curiousest, the annual deviation of the meteorological year Dec 1739 to Nov 1740 is even more significant (and the calendar year 1740 even more so!):

The annual mean temperature for 1740, at 6.93C was 3.72 SDs below the 75-year running mean of 9.21C. That is, a year as cold as 1740 would be expected to occur only once in 10,000 years!

The Jones and Briffa paper

Of course, winter 1740 has not escaped the attention of climate researchers. It was a catastrophe for Ireland, as J&B note. But J&B can only scratch their heads, noting in their Abstract that:

“Apart from evidence of a reduction in the number of explosive volcanic eruptions following the 1690s, it is difficult to explain the changes in terms of our knowledge of the possible factors that have influenced this region during the 19th and 20th centuries. The study, therefore, highlights how estimates of natural climatic variability in this region based on more recent data may not fully encompass the possible known range.” [My stress]

Fascinating though their paper is, J&B merely describe the meteorological conditions that occurred around 1740. The authors barely speculate on the underlying cause.

It turns out that winter 1739-40 was merely the second in a series of 6 winters when a strong high pressure developed over Scandinavia. In several of these years this high extended far enough west to block the usual westerlies over the UK. In the UK and Ireland, the period was generally dry as well as cold.

Lasting Effects of Cold Winters?

The dramatic winter of 1739-40 was just one in a series of 6 atypical winters. This set me thinking. We don’t have full instrumental records for 1740, but we do for less dramatic later examples, such as the cooling from around 1940, the start of another series of cold winters. Here’s a hypothesis: could it be that the entire Northern Hemisphere (NH) could naturally gain heat (over and above underlying global warming) for a few years, which is then dispersed in cold years?

In a cold winter, compared to the normal circulation in the Arctic, air mixes with that from lower latitudes. High pressure over continental land-masses (Canada, Greenland, Eurasia) pumps warm air further into the Arctic region than usual – Vancouver on the US west coast had a record mild winter for its Olympics this year – cools it and sends it south again – to northern China, the US East coast, and to the East of Greenland. The Arctic this winter was 7C warmer than usual.

The net effect must be that more heat is radiated away than in a usual winter. Maybe the climate modellers can calculate how much more.

One thing I can calculate reasonably easily, though, is one of the indirect effects. I’m taken by the persistence of cold winters. It follows that – as well as there being more of it – the snow will melt later in the spring. My weather book (Barry & Chorley) reveals that the NH regions with 4 to 8 months snow cover extend over 10s of millions of square kilometers of NH land areas. What if 10m km2 snow cover persists for just one extra week? Besides taking extra energy to melt (which turns out to be relatively insignificant), such a surface would reflect around 50% of incident sunlight relative to a year when the snow cover melted earlier. At the latitudes (between about 60N and 40N) we’re talking about, a rough, order of magnitude, estimate is that at least 100W/m2 extra energy could be reflected (or used just in melting the snow) for a week. 10m km2 is about 1/25th of the total NH surface, so the snow effect alone is of the order of a negative forcing of around 4W/m2 over the entire NH surface, that is, more than the additional forcing of greenhouse gases, but only for one week of the year. But if my calculation is too conservative, and in fact it’s several weeks over 20m km2 then we could be talking about a serious feedback. One cold winter might make it more likely that the next winter is also cold.

Triggers and Feedbacks

I suggested in my previous posts on the topic of the AMO (Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation) that the cycle is intrinsic to the system.

Indeed, cyclic behaviour is a feature of ice-sheets. During the last ice age (and previous ones) there were a number of Heinrich events – discharges of ice-bergs from the Laurentide ice-sheet over Canada. Brian Fagan in The Long Summer (p.47) gives this description:

“… the ice became thick enough to trap some of the earth’s heat, which thawed the base. Mud, stones, and water resulting from the thaw allowed the ice to skate, as it were, across the underlying bedrock. In a matter of a few centuries, Hudson Bay purged itself of the accumulated ice. Eventually, the ice thinned enough for the cold surface layers to freeze again… A Heinrich event, then, is a feed-back loop – a quick warming that causes its own end in a quick cooling.” [My stress]

I suggest a much quicker – decades rather than millennia – cycle could take place for Arctic sea-ice, with the common characteristic of “warming causing its own end”.

But it’s not quite as simple as that.

First, cooling events, such as volcanic eruptions which put a sunscreen into the stratosphere, or increased warming – fewer than normal eruptions, or increased greenhouse gas levels – will affect the wavelength of the cycle. For example, cooling during a warming phase, when the Arctic ice is thinning, will extend the time until the cooling phase.

Second, there will come a point when the system is close to tipping and a sudden cooling event (warming events are more gradual) could trigger the transition from a warming to a cooling phase.

The paper by Jones and Briffa I discussed earlier mentioned an absence of volcanoes around 1740, but my textbook, Barry & Chorley, does include a graphic (Fig 2.11, p.21) showing an unidentified eruption in around 1739 (as well as a couple in the late 1720s and nothing else after 1700). Perhaps an eruption triggered the 1739-1745 cooling phase.

Alternatively, the turn of the sunspot cycle – i.e. from increasing to decreasing insolation – might provide a trigger. Barry & Chorley (Fig. 3.2, p.35) show a sunspot cycle peaking in around 1738. Triggering by a combination of events is also possible, of course.

Once established, a cooling event will be self-sustaining as long as the cooling proceeds faster than underlying warming. I suspect the thermostat is the Arctic sea-ice. If warm North Atlantic water melts enough of it again the summer after a cold winter in Europe, then the conditions exist for another cold winter – more cooling is needed to restore equilibrium. On the other hand, if the ice cover increases, this may be enough to tip the balance back. Warm water will start to melt the ice from below, starting the cycle again.

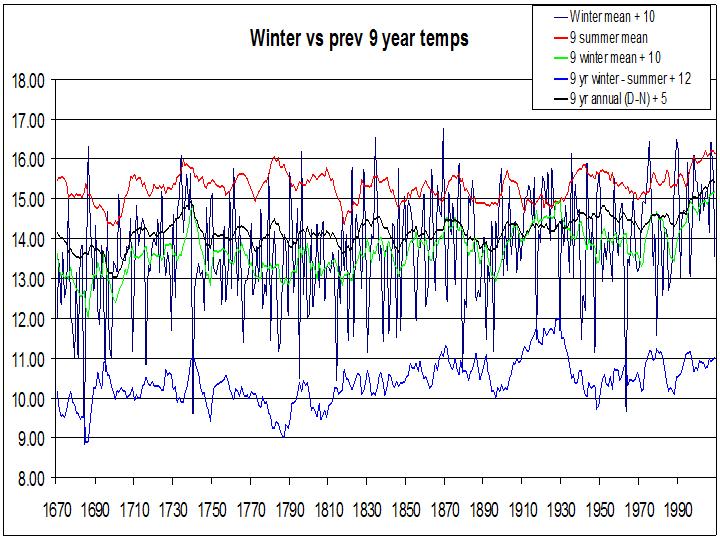

I finish with a fairly ad hoc graphic, showing winter temperatures in the CET record against annual and summer temperatures (values adjusted so that the plots appear on the same graph):

Note the wide fluctuation in the difference between winter and summer temperatures (blue line) which, at 3C, exceeds that of annual, summer or (excepting the period before 1700) winter temperatures which have varied by only 2C. When the difference is small (i.e. the winter is mild, shown by a larger value in the Figure), as in 1740 and especially the 1930s, and vice versa, this represents an imbalance that must correct itself. As can be seen in the Figure, the difference at present is small, but the disequilibrium is not as great as in the 1930s. On the other hand, global warming is expected to moderate winters more than it warms summers…

Because there are so many variables in the system, every cooling event will be different. I wouldn’t rule out another cold winter next year, though!

———

9/3/10: Corrected serious typo (“even more anomalous than the 1739-40 winter” not “the 1939-40 winter”!)

[…] asked in a previous post: “What if 10m km2 snow cover persists for just one extra week? Besides taking extra energy […]

Pingback by That Snow Calculation « Uncharted Territory — March 22, 2010 @ 4:55 pm

[…] in 1740 And All That I looked at a historical example of a sudden switch from mild to cold winters in NW Europe. The […]

Pingback by On Climate, and Causes in Complex Systems « Uncharted Territory — April 27, 2010 @ 6:23 pm

[…] Winter. Regular readers will be aware of my interest in the question as to whether winters like those of yore could occur today. I’m not expecting a Frost Fair (because we’re keeping the Thames […]

Pingback by Hey, Who Moved Greenland? « Uncharted Territory — December 6, 2010 @ 4:53 pm

This post is the topic of a thread at The Weather Outlook where some comments appear.

Comment by Tim Joslin — December 31, 2010 @ 4:43 pm

And it’s also been featured at WeatherBanter.co.uk where one or two passersby have also left some feedback.

Comment by Tim Joslin — January 5, 2011 @ 6:39 pm

[…] rare for the year of an eruption to experience a cold NH winter. This is what I naively expected when I first started looking at the Central England Temperature (CET) record – eruptions cool the planet, so winter should be colder, right? But in fact cold winters do […]

Pingback by Drill Ice, Baby, Drill Ice – Reflections on Clive Oppenheimer’s Eruptions that Shook the World « Uncharted Territory — September 23, 2011 @ 4:03 pm

[…] March, but it seems to me we’re ill-prepared for an exceptional entire winter, like 1962-3 or 1740. And it seems such events have more to do with weather-patterns than with the global mean […]

Pingback by March 2013 WAS equal with 1892 as coldest in the CET record since 1883! | Uncharted Territory — April 8, 2013 @ 4:38 pm

There’s no doubt about that – the 1962/1963 winter in the British Isles had nothing whatsoever to do with global mean temperatures, as you can see at ‘http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/service/global/map-land-sfc-mntp/196212-196302.gif’. If anything, the global temperature for the 1962/1963 winter would have been a little above normal due to abnormal warmth in Central Asia, the Bering Sea region, western Greenland and British Columbia, not to mention during the summer in southern South America. Compare this with the winter of 1971/1972, which was much warmer over the British Isles but colder globally due to low temperatures throughout Canada and Alaska.

Comment by Julien Peter Benney — September 14, 2015 @ 3:12 pm